Being a parent opens your eyes to a few things. You realize how far the USA lags behind other countries in family leave and child care, which is a grossly unfair burden in particular on moms who want to work. You see that youth sports are fun up through, say, age 8, and the whole thing turns into a cesspool that forces you to do a bit of work just to find something that isn’t dehumanizing.

And you get a look at college admissions. It’s not pretty.

In a sense, it’s a good problem to have. For all the anti-intellectualism running through America these days, tons of kids want to go to good schools, and many of them are qualified. We really need to start looking at colleges the same way we’re looking at women’s soccer these days — the “elite” is growing in number. Schools that used to attract kids with 1100 SATs and no AP classes are now picking up exceptional students who would’ve gone to top-10 schools 20-30 years ago.

But being a parent helped me discover something I didn’t expect. The stereotype of youth sports parents is that they’re foolishly spending a ton of money without realizing college soccer scholarships are rare. Wrong. They’ve done the math. They know most men’s soccer scholarships are partials, and it’s worse in other sports.

They’re spending tons of money on sports to get their kids in the door.

We’re not talking about basketball players or football players who are just being fast-tracked to the pros. There’s a reason why a big part of the bribery scandal that broke this week is about sports.

Pardon me for sending you to SI’s browser-crashing site, but they have a pretty good roundup of the details. The allegations here are that kids are designated as rowers, tennis players or lacrosse players when they are not. That’s enough of an edge to get someone into a good school.

And yes, we’re talking Ivy League schools, even as they tout their “no athletic scholarships” purity. Here’s former Yale admissions officer Ed Boland, speaking to the Associated Press:

There are what we called ‘hooked’ students and ‘unhooked’ students. Hooked students have some kind of advantage, either from an underrepresented geographic area, a recruited athlete, son or daughter of an alumnus or alumna or an underrepresented ethnic group. Athletes certainly enjoy preferential treatment in the admissions process.

(“Underrepresented geographic area,” incidentally, is what kills, say, those of us who live in Northern Virginia. My town’s high school, with an average SAT more than 150 points above the national average, reports no one going to Harvard, Yale, Princeton and Dartmouth in recent years. The data isn’t complete, but we’re talking about kids with a 4.36-4.55 GPA and a 1590-1600 SAT. Anecdotally, what I’ve seen is that the elite schools love the science and technology magnet and look at everyone else as if there’s something wrong with them. If we moved somewhere, our kids would have a better chance of getting into an elite school or a state flagship. The “scattergram” showing the scores of those accepted or rejected from our school to the University of North Carolina is depressing. A 4.25 GPA and 1500 SAT is borderline at best. Even in-state at the University of Virginia, you likely need a 4.0 and, say, a 1400, according to the scattergrams that I sincerely hope are skewed by some sort of selection bias.)

The Harvard Crimson took a candid look at athletes’ admissions in their own school, based on a couple of studies on the topic. What they found:

- Harvard assigns applicants an academic ranking from 1 (highest) to 6.

- Among candidates assigned a 1 or 2, 16% of non-athletes were accepted. Athletes? 83%.

- Among candidates assigned a 4, non-athletes’ rate was a minuscule 0.076%. Athletes? 70.46%.

Obviously, this can’t be limited to football and basketball players. (No, I don’t think the top three basketball recruits in the country last year, all of whom are currently enrolled at my alma mater, all just happened to have 1400s and 4.0s.) To an extent, we’re talking about all sports.

To be fair, the typical rowing recruit probably doesn’t have a 700 SAT and a 2.0 GPA. If you’re assigned a “2” in Harvard’s academic ranking, a special skill surely helps you get in.

And that special skill might not be sports. I took a music composition class at Duke that had two people, and the other kid was basically recruited for music. That was humbling. Nice guy, though. Some kids also have some unusual trait that makes them outstanding — a first-generation American who didn’t know English at age 10 but scrambled to a 1400 SAT, someone who started a tech company or published an academic paper, etc.

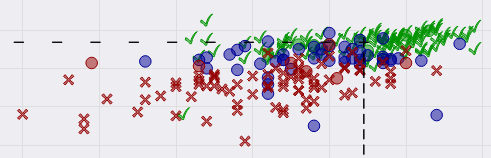

That said, check out this school’s applicants from my town’s school:

The big cluster is around 4.35 and 1440. And yet there’s one green mark for a 3.41 and 1210. That might be a stretch for a legacy unless that kid’s family has a building named after it or was an Emmy nominee. (See Claire Danes’ Saturday Night Live monologue.)

Surely, the schools that play Division III schools are exempt from all this, right? No athletic scholarships there, and probably no preferential admission, right?

Here’s something that makes me skeptical. This is the Directors Cup (overall athletic excellence) chart for Division III last year.

Williams always wins this thing. Emory is in the top four for the first time.

This is the best result for MIT. But it’s not exactly a fluke. They were 11th the previous year. The year before, sixth. In 2014-15, third behind Williams and Johns Hopkins, which is D3 in everything except lacrosse.

I can’t tell whether these schools are getting ahead because of recruiting and preferential admissions. No one from my local school’s scattergram got into MIT, either. (Seriously? Have you met the kids from this school? Take a closer look, admissions people.) Hopkins took a 4.16 / 1350 student, which isn’t exactly horrible.

What does MIT say about it? The site isn’t really clear. They say athletes are subject to the same “rigorous, academically-focused admissions process” as everyone else, but they also are “always looking for students-athletes.”

Yes, “students”-athletes. Insert joke about engineers’ writing skills.

But coaches can indeed advocate for athletes who might “contribute to MIT’s varsity athletics.” So, again, athletes have an edge. MIT isn’t going to take a kid with a 500 math SAT, but if you have a 700, maybe getting that 8k cross-country time under 26 minutes will help.

This isn’t new. The valedictorian from the class ahead of me in my small college-town private school didn’t get into Yale despite astronomical numbers. A guy who wasn’t near the top of the class got into Princeton, where he nearly made the varsity basketball team that nearly became the first 16th seed to knock off a No. 1 seed in 1989. (I still think Alonzo Mourning fouled that guy on the final shot.)

So … is this fair?

I don’t know. My kids aren’t going to play high school sports, so I might have a bias. Then again, I write about sports, so maybe I’m biased the other way. When I see Duke and Virginia play women’s soccer, I might forget that some of the players’ SAT scores are 100 points or so below the incoming class average.

But I can tell you this — the race to get kids to shore up their academic resumes really doesn’t help make youth sports a pleasant experience. Parents are a little more cut-throat when a place at Harvard or Virginia might be at stake.

Sports, we often hear, are a way out of poverty for many people. Let’s not kid ourselves. The kids getting into these schools as gymnasts, swimmers, golfers and, yes, soccer players (often) have parents who shell out plenty of cash on travel programs and private coaches.

So the rich are getting richer. And they’re turning youth sports into bloodsport.

And that stinks.